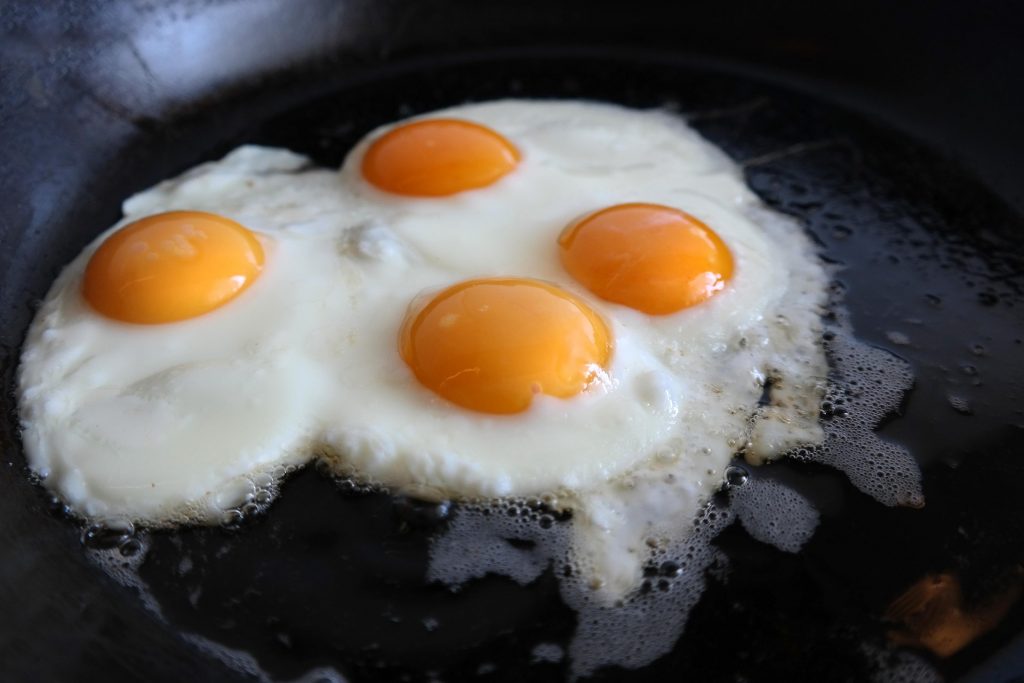

The classic 1980s anti-drug TV ad This is your brain on drugs may not be familiar to some readers, given their age. Personally, I didn’t even know about it until my undergraduate advertising class.

I can see why the ad is considered one of the best public health ads ever. The sizzling egg in the pan, the short quippy copy, it has a way of painting a pretty memorable picture.

Setting aside Regan’s War on Drugs for the time being, the cracked egg in the pan actually serves as another powerful metaphor.

This is your brain on change.

The amount of change we are encountering in society right now is extraordinary. It is happening at all levels and sectors. I am personally witnessing it in government, healthcare, and higher education, industries that I am intersecting with on a regular basis. It feels overwhelming, particularly when coupled with a steady barrage of information on social media. Some of this change is brought on by technology, economics, or political polices, but other changes emerge from the convergence of many combined factors, including organizational leaders. These changes can create feedback loops that tend to energize greater change and increase instability or rogue waves, which result from multiple smaller changes forming an unpredictable and significant disruption.

The rate of change, and the fact that it often feels like it is coming from all angles, is exhausting. Our brains like to predict what is coming next so they can keep us out of harm’s way. This is a great feature when we are dodging sabertoothed tigers on the prairie, but when we are faced with the prolonged ambiguity and uncertainty that comes with organizational change, things can get pretty uncomfortable.

Interestingly, research shows that we are more comfortable with the certainty of a negative outcome than we are with uncertainty. We often draw upon past experiences to inform our understanding of the current moment (sensemaking), creating a more stable outlook for what is to come. Regardless, when faced with uncertainty, it is common to feel anxious, struggle to think clearly, and have less control over our emotions. We experience increases in cortisol and a decrease in dopamine in our brains, causing our overall performance to decline. All in all, this makes for a less-than-ideal work environment

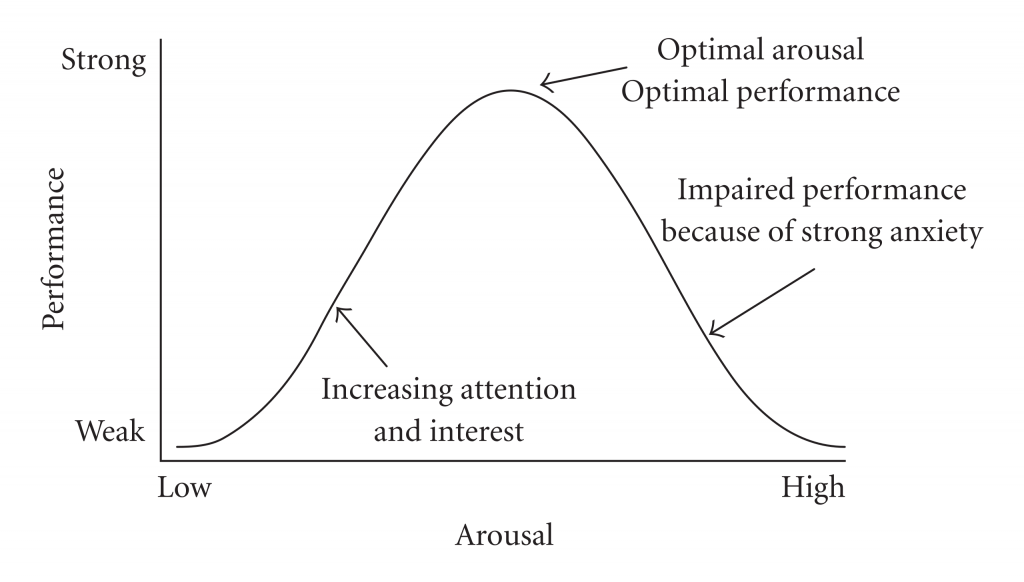

I’ve recently been reading Neuroscience for organizational change: An evidence-based practical guide to managing change by Hilary Scarlett (2016), to gain a better understanding of how leaders can help their organizations navigate times of change and disruption. Of course, I am also interested in how creativity fits into the equation as well. Change can sometimes be a valuable component of creativity and innovation. But too much change puts us in a self-protective space, making it hard to think expansively and about the future. This is best visualized using the Yerkes-Dodson inverted “U” of performance.

Being at the top of the curve is ideal; this is a space where we can achieve flow, we are positive, focused, and resilient. If we sit on the left side of the curve, we are in a space of boredom and under stimulation, and if we are too far to the right, we are in a space of distraction and stress. We think less clearly. Our cortisol is high (which can destroy brain cells), and our dopamine levels decline. Egg, meet pan.

My theory is that humans naturally seek to get into the middle of the curve as much as possible. If we are bored, we’ll seek ways to entertain ourselves. If we are stressed and overwhelmed, we will look for ways to reduce that stress. Creativity typically happens near the top of the curve. However, interestingly, sometimes a little bit of boredom or a little bit of stress can help encourage creative activities.

The problem is, however, that much of the stress that comes from change is outside of our immediate ability to control. This is also often the case with organizational leaders as well; there are limits to what can be managed internally. However, Scarlett points to several strategies that leaders can use to facilitate a healthier response to change.

1) Provide information

One of the greatest sources of anxiety for those encountering change is not knowing what will happen next. Information is crucial; we crave it, and when we don’t have it, we start to fill in the gap with our own narrative of what is going on. We exchange stories with colleagues and invest considerable energy in trying to predict the future. This has a negative impact on productivity and our mental health.

I have advised leaders on communication in times of change or crisis, and I often encourage them to provide as much information as is reasonably available as quickly as possible. The key, however, is for it to be substantive rather than just general culture statements about hard work, loyalty, and resilience. These themes can be effectively integrated into communication, provided there are valuable updates and a concrete vision for the future. Further, establishing consistent communication through modes that are most appropriate for the message and the organization is also important. These strategies build trust and can create a greater sense of certainty, reducing stress and the need to spin one’s own narrative.

2) Set short-term goals

The state of mind that comes from change can throw long-term planning and thinking out the window. Who cares about the next two years? You’re just trying to make it through the workday (or work week)! But long-range thinking is still critical for organizational success. Scarlett recommends that leaders help break down long-term goals and larger projects into smaller ones so that they feel more achievable in the moment. A six-month project may feel overwhelming right now, but if you can get one spreadsheet assembled this week, that’s a step in the right direction.

To weave in our first strategy around communication, communicating these goals in transparent and manageable terms is also key. Anchor these goals in larger messages that convey the future state of the organization. This gives members the ability to see how their goals concretely contribute to building a more certain outcome.

3) Celebrate achievements and wins

Scarlett calls on two aspects of celebration that help reinforce positive reward-seeking dopamine in our brains. The first is reminding and celebrating past achievements. Scarlett highlights how showcasing the mastery of a new skill is a way to demonstrate how an individual pushed through and learned to do something differently. This is a very powerful strategy because it demonstrates how important learning is to the equation. Creating a learning focused culture in your organization opens up new ways to stay resilient and positive in times of change.

The second aspect is celebrating wins throughout the change process and giving genuine and specific praise when people are knocking it out of the park. The key is making this a habit, which can be tough during the change process. And it really does matter. Again, Hillary points to the dopamine reward relationship. Specific praise, either from us or our colleagues, makes us feel seen and appreciated for the work we do. It helps build stronger social ties and supports psychological safety.

Reflection Questions

At the end of each chapter of the book, Scarlett outlines a few reflection questions for the reader. I have modified a few of these for you to consider as you navigate change within your own organization:

- What issues are currently causing the most anxiety among people on my team or in my organization?

- Can I provide my team or organization with more specific information at a greater frequency regarding the current change we are experiencing?

- When was the last time I highlighted or asked about past achievements?

- How can I be more specific when I highlight individual, team, or organizational wins?